In 2000, economist Steven Levitt and sociologist Sudhir Venkatesh published an article in the Quarterly Journal of Economics about the internal wage structure of a Chicago drug gang. This piece would later serve as a basis for a chapter in Levitt’s (and Dubner’s) best seller Freakonomics: A Rogue Economist Explores the Hidden Side of Everything (P.S.) The title of the chapter, “Why drug dealers still live with their moms”, was based on the finding that the income distribution within gangs was extremely skewed in favor of those at the top, while the rank-and-file street sellers earned even less than employees in legitimate low-skilled activities, let’s say at McDonald’s. They calculated 3.30 dollars as the hourly rate, that is, well below a living wage (that’s why they still live with their moms). [2]

If you take into account the risk of being shot by rival gangs, ending up in jail or being beaten up by your own hierarchy, you might wonder why anybody would work for such a low wage and at such dreadful working conditions instead of seeking employment at Mc Donalds. Yet, gangs have no real difficulty in recruiting new members. The reason for this is that the prospect of future wealth, rather than current income and working conditions, is the main driver for people to stay in the business: low-level drug sellers forgo current income for (uncertain) future wealth. Rank-and file members are ready to face this risk to try to make it to the top, where life is good and money is flowing. It is very unlikely that they will make it (their mortality rate is insanely high, by the way) but they’re ready to “get rich or die trying”.

With a constant supply of new low-level drug sellers entering the market and ready to be exploited, drug lords can become increasingly rich without needing to distribute their wealth towards the bottom. You have an expanding mass of rank-and-file “outsiders” ready to forgo income for future wealth, and a small core of “insiders” securing incomes largely at the expense of the mass. We can call it a winner-take-all market.

Academia as a Dual Labour Market

The academic job market is structured in many respects like a drug gang, with an expanding mass of outsiders and a shrinking core of insiders. Even if the probability that you might get shot in academia is relatively small (unless you mark student papers very harshly), one can observe similar dynamics. Academia is only a somewhat extreme example of this trend, but it affects labour markets virtually everywhere. One of the hot topics in labour market research at the moment is what we call “dualisation”[3]. Dualisation is the strengthening of this divide between insiders in secure, stable employment and outsiders in fixed-term, precarious employment. Academic systems more or less everywhere rely at least to some extent on the existence of a supply of “outsiders” ready to forgo wages and employment security in exchange for the prospect of uncertain security, prestige, freedom and reasonably high salaries that tenured positions entail[4].

How can we explain this trend? One of the underlying structural factors has been the massive expansion in the number of PhDs all across the OECD. Figure 1 shows the proportion of PhD holders as a proportion of the corresponding age cohort in a number of OECD countries at two points in time, in 2000 and 2009. As you can see, this share has increased by about 50% in 9 years, and this increase has been particularly pronounced in countries such as Portugal, Greece or Slovakia, where it nearly tripled, however from a low starting level. Even in countries with an already high share, the increase has been substantial: 60% in the UK, or nearly 30% in Germany. Since 2000 the number of OECD-area doctorates has increased at an average of 5% a year. [5a]

So what you have is an increasing number of brilliant PhD graduates arriving every year into the market hoping to secure a permanent position as a professor and enjoying freedom and high salaries, a bit like the rank-and-file drug dealer hoping to become a drug lord. To achieve that, they are ready to forgo the income and security that they could have in other areas of employment by accepting insecure working conditions in the hope of securing jobs that are not expanding at the same rate. Because of the increasing inflow of potential outsiders ready to accept this kind of working conditions, this allows insiders to outsource a number of their tasks onto them, especially teaching, in a context where there are increasing pressures for research and publishing. The result is that the core is shrinking, the periphery is expanding, and the core is increasingly dependent on the periphery. In many countries, universities rely to an increasing extent on an “industrial reserve army” of academics working on casual contracts because of this system of incentives.

Varieties of Dualisation

What I mention above is the broad dynamic that spans across a number of countries. However, the boundary of the insider and outsider group varies across countries. I can give a number of examples from different countries.

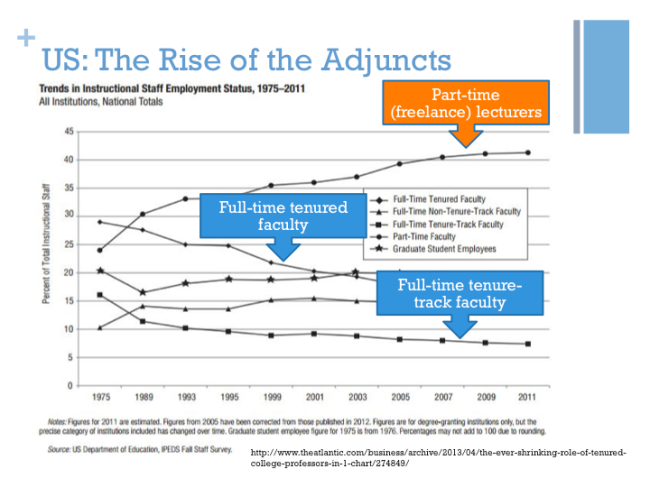

In the United States, numbers from the department of education reported in The Atlantic (Figure 2) show that more than 40% of teaching staff at universities are now part-time faculty without tenure, or adjunct lecturers paid per course given, with no health insurance or the kind of other things associated with a standard employment relationship.[5b] As you can see from the graph, the share of permanent tenured faculty has shrunk dramatically. This doesn’t mean that the absolute number of faculty has diminished, it has actually increased substantially, but it has been massively outpaced by the expansion of teaching staff with precarious jobs and on low incomes. The Chronicle of Higher Education recently reported about adjunct lecturers relying on food stamps.[6] The person mentioned in the article declares a take-home pay of 900$ per month, which is sadly not that far away from the 3$ hourly rate of the drug dealer, but for a much more skilled job.

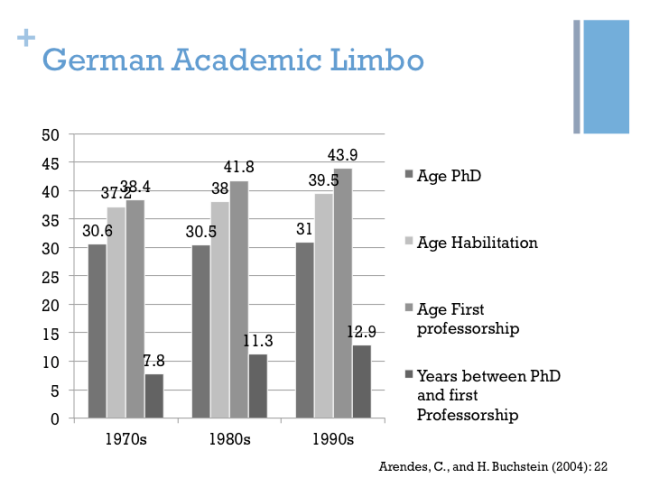

Germany is another case where there has traditionally been a strong insider-outsider divide, essentially because of the hourglass structure of the academic job market. On the one hand, there are relatively good conditions at the bottom at the PhD level, and opportunities have expanded recently because of massive investments in research programs and doctoral schools generating a mass of new very competitive PhDs. On the other hand, there are good jobs at the top, where full professors are comparatively well paid and have a great deal of autonomy. The problem is that there is nothing in the middle: for people who just received their PhD, there is just a big hole, in which they have to face a period of limbo in fixed-term contracts (wissenschaftliche Mitarbeiter) or substitute professor (Vertretungsprofessur) for a number of years, after which they can hope to get their first permanent job in their mid-40s, while this could happen ion their mid-30s in the 1970s.[7] Figure 3 shows the average age of the PhD, for the habilitation and the first professorship in political science between the 1970s and 1990s. The age of the PhD hasn’t changed that much but the age of the first professorship has increased substantially. Also, you have to take into account that there is a selection effect because the people in the sample are only those who have made it to the professorship, and doesn’t take into account all of those that have dropped out during the academic limbo. What is interesting is that the insiders (professors) who control the market have often been hired at a time when no such competition existed, and you may wonder if they themselves would have been hired if similar market conditions had been in place. A number or new types or positions in the middle, such as the Juniorprofessuren have ben created, but these are also limited in time and are not the equivalent of tenure-track positions. Germany is the country of financial prudence, and both regional and federal governments have been reluctant to commit themselves to fund programs and positions on a permanent basis.

This academic limbo is accentuated by the fact that in some disciplines it has become common to apply for professorships even if you’re already a tenured professor so that you can negotiate your own working conditions with your home university. The result of this is that it is very difficult for recent PhDs to compete with established professors, and hiring processes tend to last a very long time as many candidates refuse and take time to bargain back and forth. Time, you may have it if you are tenured, but you don’t if you have an insecure position. You cannot wait two years when a university is negotiating with somebody who will eventually refuse if you have fixed-term contracts. This is a really perverse and insider-oriented system.

The United Kingdom is different from Germany in the sense that it does have intermediate permanent positions for people finishing their PhD. Britain is the biggest academic market in Europe and lectureships provide secure employment for relatively young academics even if the starting salary is relatively low if you take into account living costs, especially in London. However, this does not mean that UK higher education does not rely on a large industrial workforce of outsiders as well. Recently, the Guardian reported on the prevalence of so called “zero-hour contracts” at UK universities. [8] These are contracts which do not specify the number of hours one is supposed to give, and basically imply that the workers needs to be available to her employer when there is work. Compared to Continental Europe, what is striking is the pretty dismal situation of PhD students and teaching assistants who provide quite a large part of the teaching and whose employment conditions are much more casual than what one can see elsewhere. When I did my PhD in Switzerland, I was basically a public employee with a corresponding salary, pension contributions, welfare entitlements. A large proportion of PhD students in the UK do not have regular sources of funding, need to apply here and there to get scholarships, and when they teach they are paid per hour taught or a piece rate (exam/essay marked) that can vary across and even within universities.

The number of hours usually taught at UK universities is relatively moderate, at least at Russell-Group universities, because of a heavier focus on essays and independent work from students, but also partly because departments can rely on this flexible workforce. This has been accentuated by the strong constraints set on universities in terms of research and publication through the REF (Research Excellence Framework). This happens through two channels. First, as research is what is most valued, this creates incentives for established professors to retreat from teaching and secure research grants and publications instead, leaving teaching to casual teaching staff. On the other hand, some universities have advertised a number of temporary positions just because of the REF in order to use people’s publications in their submissions. There is no guarantee that universities are going to keep these people once they have “used” them.

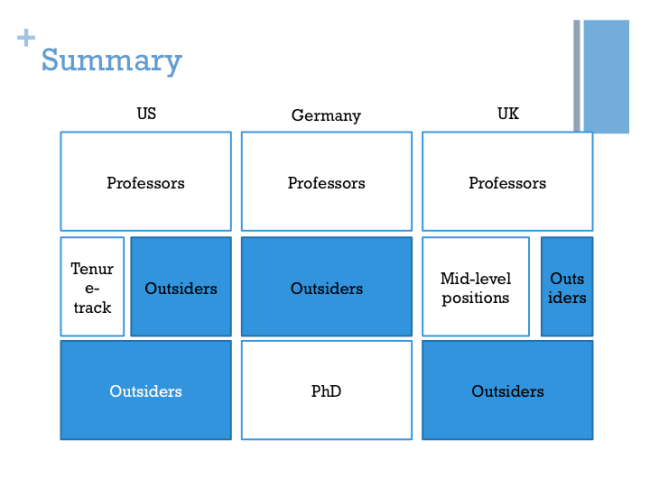

Figure 4 summarizes in broad terms the differences outlined above. As I can see it, this form of insider/outsider divide exists everywhere and is probably expanding. The interesting thing is that these divides are largely structural in the sense that the system simply couldn’t work without this large supply of outsiders ready to accept any kind of employment contract. If you are mobile, strategic and concerned with employment conditions, you might want to exploit these differences and avoid the outsider boxes at different stages of your career. This would mean avoiding the UK for your PhD and avoiding Germany after your PhD.

This was presented on November 19 at the European University Institute’s Academic Careers Observatory Conference. For an updated analysis of academic labour markets in Europe, check this this paper.

[1] Levitt, S.D., and S.A. Venkatesh (2000) “An Economic Analysis of a Drug-selling Gang’s Finances”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 115(3): 755-789; Levitt, S.D., and S.J. Dubner (2006) Freakonomics: a Rogue Economist Explores the Hidden Side of Everything. NY: HarperCollins.

[3] Emmenegger, P., S. Häusermann, B. Palier, and M. Seeleib-Kaiser et al. (2012) The Age of Dualization: the Changing Face of Inequality in Deindustrializing Societies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[4] http://www.economist.com/node/17723223

[5a] NB: This paragraph has been amended to reflect more recent data. The data can be found here.

[5b] http://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2013/04/the-ever-shrinking-role-of-tenured-college-professors-in-1-chart/274849/

[7] Data for political scientists from Arendes, C., and H. Buchstein (2004) “Politikwissenschaft Als Universitätslaufbahn: Eine Kollektivbiographie Politikwissenschaftlicher Hochschullehrer/-innen in Deutschland 1949–1999”, Politische Vierteljahresschrift 45(1): 9-31; Armingeon, K. (1997) “Karrierewege Der Professoren Und Professorinnen Der Politikwissenschaft in Der Schweiz, Österreich Und Deutschland”, Swiss Political Science Review 3(2): 1-15.

Related articles

- Higher Education is an Industry…and I’m a Factory Worker (englishstudies.wordpress.com)

- I am a disposable academic (researchfrontier.wordpress.com)

- 6 ways neoliberal education reform is destroying our college system (salon.com)

- Varieties of academic labour markets in Europe

262 responses to “How Academia Resembles a Drug Gang”

Reblogged this on Lukeskyrunner and commented:

How Academia Resembles a Drug Gang

Reblogged this on Writing a PhD Thesis.

[…] Posted on Νοεμβρίου 22, 2013 by eniaiometopopaideias Posted on November 21, 2013 […]

It has always struck me as insightful that universities go to such lengths to act out the principles of meritocracy and open recruitment for entry level positions, but hand out promotion towards the core of the ‘inner circle’, behind doors closed to the rest of institutions and wider society. It’s incredible that Heads of Schools and Departments, and upwards, in Russel Group Univetsities in the UK are given the nod – with no free and open competition for outside talent, skills and ideas. Some talk about the neoliberalisation of higher education, but this appears to exist alongside feudal structures at the moment.

Well said, Alastair. It’s disappointing, if not downright disturbing, and with no change in sight.

Sorry but having worked at a UK Russell Group university I can assure you there is no guarantee you will have moderate teaching hours. Please do not continue to perpetrate these myths. Indeed teaching only contracts are now emerging at these universities which will further divide the academic community.

[…] https://alexandreafonso.wordpress.com/2013/11/21/how-academia-resembles-a-drug-gang/ […]

[…] came across this excellent, must read piece on FB yesterday from the blog of King’s College London political economy professor Alexandre […]

[…] https://alexandreafonso.wordpress.com/2013/11/21/how-academia-resembles-a-drug-gang/ […]

[…] I had this wonderful piece tweeted in – I think the first one was Kate Clancy – Alexandre Alfonso on how Academia resembles a drug gang. An inspiration for him was a chapter in Freakonomics where they discuss what is the allure of being […]

[…] Today, I had this wonderful piece tweeted in – I think the first one was Kate Clancy – Alexandre Alfonso on how Academia resembles a drug gang. An inspiration for him was a chapter in Freakonomics where they discuss what is the allure of being […]

This is a good start, but it is very incomplete unless you account for the bloated administrators who often outnumber the TT faculty, and the swollen ranks of support staff who may only tangentially offer services that support student instruction. Those are also the people who make a living telling TT faculty to do more with less, and who control the hiring of new lines and the replacement of old ones.

[…] John Protevi The hook is a little facile, but the analysis of “dualisation” is good. via Facebook https://alexandreafonso.wordpress.com/2013/11/21/how-academia-resembles-a-drug-gang/ […]

Reblogged this on As the Adjunctiverse Turns and commented:

not just in the U.S.: some (but not all) global aspects of academia’s dual labor market

Well, I certainly don’t agree with your comments about the inadvisability of doing a PhD in the UK. At least in the sciences PhD students get a pretty decent grant, and don’t (in my University anyhow) have to do much teaching at all (and what they do provides extra income). The average age of a science PhD award for a non-mature student (around 25/26) is hugely more favourable than compared to a German PhD completer who, from your Figure above is already 30 years old!

One needs to ask “why do I want to do a PhD”? It’s not a job! It’s a fantastic opportunity to do original research and to develop one’s independent research, study, creative and scholarship skills. In the UK you can do this in a concise 3-4 year period after which you can take your career wherever choice/necessity takes you – it could be postdocing at home or abroad or something entirely different. The UK PhD doesn’t tie you down until your 30 after which your opportunities become much more proscribed.

Our cohort of PhD students are pretty much as well off now on their grants as I was 30 years ago when I was doing my PhD. I didn’t accumulate any money then and they don’t now, but that’s hardly the point of doing a PhD.

Indeed the attractiveness of doing a PhD in the UK is rather exemplified by the number of students from abroad who choose to come to the UK to do their PhD’s (at least in the sciences).

Of course the academic career progression is as problematic as it’s always been (what to do after one’s first or second post-doc) as the more general thrust of your article indicates…

[…] Alexandre Afonso, on how higher education resembles a drug gang […]

Reblogged this on Things I grab, motley collection .

From my experience of doing a PhD in the UK, being a postdoc in the USA and now in Germany, in the areas of mathematics/engineering/biology, I agree with the gist of the article.

I also concur with Chris on PhD studentships – they’re sufficient if you get one, but e.g. EPSRC studentships require having a strong connection to the UK (living there for the past 3 years) even for EU students. If you’re from outside the EU, or are in the humanities, or e.g. in geography, funding is hard to find.

I heard that there is a developing tendency in the UK to no longer offer total job security for professors – you must trade pay rises for total job security, which most won’t do. Can somebody confirm this?

The drug gang analogy is thought-provoking (I knew about it from Freakonomics). The major difference is that PhD students should be intelligent enough (and their supervisors should make it clear at the beginning), that just as not every BSc graduate becomes an MSc and not every MSc is accepted to do a PhD, not every PhD can stay in academia to do a postdoc. And not every postdoc will become tenured faculty. Completing a funded PhD does little harm to a young adult and their prospects if they prepare themselves for a change in career course.

The rise of the adjunct professor is very concerning, if these people were misled about their career prospects.

[…] In 2000, economist Steven Levitt and sociologist Sudhir Venkatesh published an article in the Quarterly Journal of Economics about the internal wage structure of a Chicago drug gang. This piece wou… […]

The more appropriate comparison is with the development of the two tier contract that started to emerge in the retail sectors in North American and other labour regimes that permitted this. The problem with the eye-catching and provocative comparison with drug gangs is the implication that those with tenured/tenure-stream positions are the people with the power making the decisions to keep an insider/outsider dynamic in play. What the history of the two tiered labour contracts show in the retail sector is that eventually the ‘protected’ workers with higher wages/better benefits are angled out and the new labour arrangements are established at the level of the more precarious set of conditions.

The underlying issue is, I would argue, linked to two aspects of the late capitalist global economy – a drive toward de-skilling and undermining workers/employers that is inherent in an accumulation-based market economy and the rise of credentialism as a gate keeping mechanism to limit completion to scarce employment options. It is not simply in the academic sector that one sees this. For example, over the course of the late 20th century in North America high school graduation has become a minimum certificate and many jobs that previously were accessible with a high school diploma now require an undergraduate degree, and so it goes.

Hear hear! Right on target.

I’m not a big freakonomics fan, and this post doesn’t seem very helpful to me. It’s clever, but it reduces a complex legal-social-political-ethical phenomenon to a simple supply and demand problem, again, with a few clever tweaks. It doesn’t give anybody any tools with which to fight back. We might as well throw in the towel. The way I read it, there is no rational basis on which to challenge the insider-outsider problem, because everyone is acting rationally, in their self-interest, and so-forth, and it all seems as though things like the Fair Labor Standards Act and its implementations, interpretations and frustrations, and all of organized labor history, and any culturally shared values of equity…. to begin with–make your own list—are just so much flotsam on a great ocean of eternally efficient market mechanisms. And BTW, quoting The Atlantic quoting Dept. of Education’s IPEDS data? Rookie move.

[…] How Academia Resembles a Drug Gang | Alexandre Afonso […]

Reblogged this on Swift, like Shadows and commented:

I like the exploration of the structure here. It’d be interesting to see this structure explicitly connected with the experiential aspect of being a CI or of being part of that level of ‘outsiders’ to the inner-circles of Gang Academe: where your ‘customers’ (students) have an awful lot of power over your ability to stay employed in the short term (get it, term? Because CI’s are usually employed semester-to-semester or term-to-term), but you also face considerable interpersonal violence (psychological and economic) from your rivals and fellow low-level ‘gangsters’: I’d bet that unless we’re talking about a very rare institution where low-levels band together in a circle of mutual assistance (no, not a union, more like voluntary aid and friendship), we probably tend to see a lot of the threat going on between lower-levels. Academic mobbing, workplace bullying – I’ve seen it happening among grad students and it’s ugly, ugly, ugly… it can’t just be a ‘culture of bullying seeping into academia’ thing – I’d bet it’s quite strongly related to this economic structure too.

My ruthless criticism.

The figures are blurry. Only one figure has the axes labeled (and it’s just one axis). None has a sensible title. None has an obvious caption. The acronyms in Fig 1 are not defined. “Corresponding age cohort” is not defined.

[…] Con un título muy llamativo, se llama la atención sobre la fragilidad para el acceso a la profesión de docente universitaria en algunos países importantes […]

Reblogged this on Mae Mai and commented:

This could just as easily be said about the arts (and interestingly the same effect has been observed in the pop music industry).

[…] Con un título muy llamativo, se llama la atención sobre la fragilidad para el acceso a la profesión de docente universitaria en algunos países importantes […]

Reblogged this on The truth is in the details and commented:

Brilliant analogy.

Reblogged this on Chicano Conversations.

A reblogué ceci sur Ritachemaly's Blog and commented:

you have is an increasing number of brilliant PhD graduates arriving every year into the market hoping to secure a permanent position as a professor and enjoying freedom and high salaries, a bit like the rank-and-file drug dealer hoping to become a drug lord. To achieve that, they are ready to forego the income and security that they could have in other areas of employment by accepting insecure working conditions in the hope of securing jobs that are not expanding at the same rate

[…] artigo foi publicado originalmente aqui por Alexandre Afonso, lecturer no Departamento de Economia Política do Kings College […]

[…] small (unless you mark student papers very harshly), one can observe similar dynamics.” It’s all about a limited supply of posts and an ever-increasing flow of would-be professors. And you don’t […]

It is an interesting question how far this dualization of academic employment is the result of genuinely free market forces. It may be rational for the as-yet-untenured to work for nothing in the hope of future luxury, but why do the customers for academic services put up with this?

Insofar as these customers are students (as opposed to research sponsors), they want teaching from high-level academics, not from overstretched casuals. Classes are not like drugs in that respect–it matters to the customer who supplies them.

And we do see this market pressure working against dualization. This is why non-research liberal arts colleges flourish in the States, and why the new competitive undergraduate fees regime in the UK is currently pushing universities to offer more contact hours from senior tenured faculty.

But I suspect this pressure will have a limited impact on the more elite research institutions, because of their semi-monopoly in prestige. If prestige is what the students want, the tenured academics who hold the power in the elite universities can continue exploit their market position, and feather their nests without driving the students away.

Terrific analogy. And as to the comment about not earning a Ph.D’s to become wealthy misses the point completely. We get them so we can research or teach–rarely does anyone have the luxury of getting one just for the knowledge. Few today expect to be wealthy doing so, but people have to eat and have a roof over their heads. Thirty years ago, that wasn’t a problem. Today it The majority of teachers in higher ed in the US are precarious.

Sorry about the typos in my comment.

[…] A group of hybrid thinkers would inevitably reshape academic anthropology, if they were accorded democratic participation and a living wage. Anthronauts work against the anti-social nature of anthropology: going “into the field” to do […]

[…] I’m describing what the job is like once you get the job. When Alexandre Afonso goes into great detail about how academia resembles a drug gang (and to be honest, I’ve only the Inside Higher Ed piece) or when Nate Kreuter claims that the […]

[…] Con un título muy llamativo, se llama la atención sobre la fragilidad para el acceso a la profesión de docente universitaria en algunos países importantes […]

[…] This article discusses the economics of academia. It has an interesting comparison of systems in the US and Europe. One thing it fails to discuss is the impact of online education: how is the army of contract labor changing as teaching is made non-site-specific? How is the position of professors changing in response? […]

[…] I just read these thought-provoking reflections in this blog: https://alexandreafonso.wordpress.com/2013/11/21/how-academia-resembles-a-drug-gang/ […]

A fascinating comparison between drug gangs & academic life. Your description of the economics of both and the similarities between them is compelling. You could extend that description to more and more areas of contemporary life. What you describe is a capitalism, red in tooth and claw, of an ilk similar to that which we saw spring up in Post-Communist Russia in the 1990s. Does the Rule of Law and the structures of Civil Society enjoyed at present in advanced Western Societies mean that we will not see the descent into rule by Mafia, Oligarchs and a state that is either an ally or competitor to these but operates by the same rules of engagement? Or are you describing a gradual descent into such a way of life? Perhaps your comment that at least academics are less likely to be shot than drug gang members may yet prove to be hopelessly optimistic.

[…] "So what you have is an increasing number of brilliant PhD graduates arriving every year into the market hoping to secure a permanent position as a professor and enjoying freedom and high salaries, a bit like the rank-and-file drug dealer hoping to become a drug lord. To achieve that, they are ready to forgo the income and security that they could have in other areas of employment by accepting insecure working conditions in the hope of securing jobs that are not expanding at the same rate. Because of the increasing inflow of potential outsiders ready to accept this kind of working conditions, this allows insiders to outsource a number of their tasks onto them, especially teaching, in a context where there are increasing pressures for research and publishing. The result is that the core is shrinking, the periphery is expanding, and the core is increasingly dependent on the periphery. In many countries, universities rely to an increasing extent on an “industrial reserve army” of academics working on casual contracts because of this system of incentives." [via @LinaMorgado] […]

[…] See on alexandreafonso.wordpress.com […]

The lack of tenure in the UK is a game changer compared to other countries. And recently many universities have changed their statutes to weaken what was left of the idea of tenure. UK academics can be threatened with their jobs. It happens frequently. The level of bullying is, therefore, much higher – some good supporting evidence for that statement in the literature.

Is there tenure (in the sense you mean) in many countries other than the US? You can get fired in the US if the university decides to close departments etc (and you need to get tenure first, which for many is in itself a game changer – and can open you up to the prospect of bullying too).

Reblogged this on Radio Interferometry and commented:

There has been some serious discussion on this topic lately, and I am seeing the effects of lack of job opportunities in academia which is leading to people dropping out after their PhDs or post-docs, many of whom, reluctantly. There needs to be a serious change in the job market for young professionals in Academia which would help in creating a healthier atmosphere.

[…] has been making the rounds and is worth a read: How Academia Resembles a Drug Gang? It’s a slightly different take on the “academia as a dual labor market” argument […]

[…] In 2000, economist Steven Levitt and sociologist Sudhir Venkatesh published an article in the Quarterly Journal of Economics about the internal wage structure of a Chicago drug gang. This piece wou… […]

[…] Considering a graduate degree for the purposes of teaching in higher education? Beware. The academic job structure is similar to that of a drug gang, and it won’t work in your favor. See here for the full story : https://alexandreafonso.wordpress.com/2013/11/21/how-academia-resembles-a-drug-gang/ […]

[…] Considering a graduate degree for the purposes of teaching in higher education? Beware. The academic job structure is similar to that of a drug gang, and it won’t work in your favor. See here for the full story : https://alexandreafonso.wordpress.com/2013/11/21/how-academia-resembles-a-drug-gang/ […]

Reblogged this on PhilosophyNews.com. Thanks!

I worked as an assistant to art professors at a community college, and can attest to the low wages for adjunct professors as well as the minimum availability of the elite tenured positions. Those professors lucky enough to have tenure clung tightly to their positions, not wanting to vacate for any reason less than death. The poor adjuncts were like vultures waiting to swoop in in the event of said deaths; and most had second and even third jobs just to pay their bills while they waited.

Part of my reason for foregoing graduate degrees in my field of art history, is the knowledge I would graduate with a HUGE debt and a tiny income. I’d rather continue studying on my own for free than pay hundreds of thousands of dollars to become an instructor who never sees any of the tuition dollars the school brings in for the class. I may never get to teach art history, but no one can stop me from learning about it!

Reblogged this on Andy's Thinktank and commented:

This concerns me because I am interested in becoming a professor one day. I guess we’ll see how it all comes out in the end.